Page 1 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

December 10, 2018

The Honorable Ken Calvert

Chairman

The Honorable Betty McCollum

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

Indian Health Service: Spending Levels and Characteristics of IHS and Three Other

Federal Health Care Programs

The Indian Health Service’s (IHS) mission is to provide health care services to American Indian

and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people who are members or descendants of federally recognized

tribes, consistent with federal law.

1

Congress has declared that it is federal policy, in fulfillment

of special trust responsibilities and legal obligations to Indians, to ensure the highest possible

health status for AI/AN people.

2

IHS, within the Department of Health and Human Services

(HHS), provides health care to approximately 1.6 million AI/AN people annually.

3

Advocates for AI/AN people have longstanding concerns about whether IHS has sufficient

funding to provide eligible individuals with all needed services, noting IHS's lower funding

relative to federal health programs for other populations (some of which include AI/AN people).

These other federal health programs include:

• The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which is part of the Department of Veterans

Affairs (VA), which provides health care services for approximately 7 million veterans

and non-veterans;

4

• Medicare, which is overseen by HHS’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

(CMS), which pays for health care services for around 58 million persons aged 65 years

and older (among others); and

• Medicaid, which is jointly administered and financed by CMS and state governments,

which pays for health care services for about 74 million low-income individuals.

1

Federally recognized tribes have a government-to-government relationship with the United States and are eligible to

receive certain protections, services, and benefits by virtue of their status as Indian tribes. The Secretary of the

Interior publishes annually in the Federal Register a list of all tribal entities that the Secretary recognizes as Indian

tribes. As of July 23, 2018, there were 573 federally recognized tribes. See 83 Fed. Reg. 34863 (July 23, 2018).

2

25 U.S.C. § 1602.

3

The 1.6 million represents IHS’s user population, that is, those individuals who accessed a federally or tribally

operated facility at least once over the past 3 years. The user population is a subset of the total service population of

2.2 million, which is IHS’s estimate of the number of AI/AN users that could access its services.

4

There are approximately 20 million veterans in total, of which 9 million are enrolled in VHA, with approximately 7

million receiving care. The 7 million receiving care are defined by VHA as “unique patients”—uniquely identified

individuals treated by VHA, or whose treatment is paid for by VHA. The unique patient population includes about

700,000 non-veterans (e.g., family members, active duty military and reservists, employees receiving preventive

occupational immunizations).

Page 2 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

You asked us to compare IHS program characteristics, including spending levels, to those of

other federal health care programs. In this report, we present information on the spending levels

and program characteristics for IHS, VHA, Medicare, and Medicaid from 2013 through 2017.

To address this objective, we analyzed budget and program documents from the four programs

for the years 2013 through 2017, such as agency budgets and Congressional budget

justifications, and reports produced by the Medicare Trustees, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment

and Access Commission, and CMS. For each program, we examined total annual spending

levels and spending on a per capita basis.

5

To do so, for IHS and VHA, we analyzed total

obligations per fiscal year. For IHS, we then calculated the per capita spending amount by

dividing the total obligations by the number of individuals served.

6

For VHA, we used data that

are presented in VHA’s annual congressional budget submission on obligations per unique

patient. For Medicare and Medicaid, we analyzed expenditure data and relied on per capita

spending data publicly available in the sources noted above.

7

For each program, we refer to

these amounts as spending or spending on a per capita basis because they represent the

agencies’ use of funds for the provision of health care services. One inherent limitation to our

analysis is that the per capita spending amount for each program does not directly account for

spending for beneficiaries who are eligible for multiple federal programs. To supplement our

analysis, we interviewed knowledgeable agency officials, and, to obtain the perspective of tribal

communities, we also interviewed representatives from the National Indian Health Board and

attended a meeting of its National Tribal Budget Formulation Work Group, which makes

recommendations to IHS on tribal budget priorities.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2017 to November 2018 in accordance

with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan

and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence

obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit

objectives.

Background

IHS, VHA, Medicare, and Medicaid are diverse programs through which the federal government

is either a direct provider of health care services or pays for services as a public insurer.

Specifically, IHS and VHA provide health care services directly to eligible beneficiaries. Both

programs provide care through agency-administered hospitals and other health care facilities,

5

The programs have differing definitions of their user populations. Therefore, we use the term “individuals served” to

encompass IHS users (individuals receiving care from a federally or tribally operated facility within the last 3 years);

VHA unique patients (uniquely identified individuals treated by VHA or whose treatment is paid for by VHA); and

Medicare beneficiaries and Medicaid enrollees (individuals enrolled in either program in a specific year).

6

An “obligation” is a definite commitment that creates a legal liability of government for the payment of goods and

services ordered or received.

7

An “expenditure” is the actual spending of money or an outlay. We calculated Medicare and Medicaid spending

using expenditures because, in contrast to IHS and VHA, Medicare and Medicaid act as public insurers, reimbursing

for services provided. Because of the differences in the four programs’ operations and structures, the data we

obtained and report on the Medicare program are on a calendar year basis, and the data we obtained and report on

the IHS, VHA, and Medicaid programs are on a fiscal year basis. Medicaid per capita spending data for fiscal year

2017 were not publicly available at the time of this report, so for that year, we calculated spending using estimates

published by CMS’s Office of the Actuary.

Page 3 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

though IHS funds also pay for care provided by tribally operated facilities.

8

These programs also

contract with health care providers outside of agency-funded facilities to provide care for users

under certain circumstances—IHS’s Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) program and VHA’s

community care programs.

9

In contrast, Medicare and Medicaid act as public insurers for their

beneficiaries by reimbursing health care providers for covered health care services or

contracting with managed care plans to pay providers for services delivered to program

enrollees.

In addition, the programs’ administrative structures and eligibility requirements differ markedly,

and they are intended to serve different populations. (See table 1 for additional information on

the programs’ administrative structures and eligibility requirements.)

8

Under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, as amended, federally recognized Indian tribes

can enter into self-determination contracts or self-governance compacts with the Director of IHS to take over the

administration of IHS programs for Indians previously administered by IHS on their behalf. See generally 25 U.S.C.

§§ 5301-5423. In 2017, IHS transferred approximately 54 percent of its total budget to tribes and tribal organizations

to operate part or all of their own health care programs through self-determination contracts and self-governance

compacts. Under the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, IHS also awards contracts and grants to non-profit urban

Indian organizations that provide health care and referral services to urban Indians.

9

VHA also has the option to purchase care from community providers through a number of community care

programs, in circumstances when a health care service is not offered at a VA medical center or cannot be provided in

a timely manner.

Page 4 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Table 1: Structure of and Eligibility for Four Federal Health Care Programs—Indian Health Service (IHS),

Veterans Health Administration (VHA), Medicare, and Medicaid

Program Item

IHS

VHA

Medicare

Medicaid

Administrativ

e structure

Direct provider.

• Within the

Department of

Health and Human

Services (HHS)

• Provides health

care services

through a network

of federally or

tribally operated

hospitals, clinics,

and health stations.

• Pays for health care

services

unavailable at these

facilities through its

Purchased/

Referred Care

program.

Direct provider.

• Within the

Department of

Veterans Affairs

• Provides services

through VHA-

administered

hospitals and other

health care

facilities.

• Pays for certain

care outside the

VHA health care

system through its

community care

programs.

Public insurer.

• Federal program

administered by the

Centers for

Medicare &

Medicaid Services

(CMS) within HHS.

• Pays health care

providers for

covered health care

services.

• Pays insurers for

health care services

delivered through

managed care

plans.

a

Public insurer.

• A joint federal-

state program—

administered by

the states, with

CMS oversight.

• Pays health care

providers for

covered health

care services.

• Pays insurers for

health care

services delivered

through managed

care plans.

a

Who is

eligible

• Members of a

federally

recognized Indian

tribe, or those who

meet certain other

requirements (e.g.,

actively

participating in tribal

affairs).

• Veterans, as

determined by a

number of service-

related factors,

such as the period

of active service,

discharge status,

and the presence

of service

connected

disabilities.

• Certain non-

veterans, such as

veterans’ spouses,

dependents, and

survivors.

• Persons aged 65

and older, certain

individuals with

disabilities, and

individuals with

certain conditions,

such as end-stage

renal disease.

• Certain low-

income

individuals, such

as pregnant

women, children,

the disabled, and

persons aged 65

and older.

b

Source: GAO analysis of program information. | GAO-19-74R

Notes: Individuals may be eligible for more than one program. For individuals eligible for IHS services, the IHS or tribally operated

facility may be reimbursed by VHA, Medicare, and Medicaid for care provided. When approving funding for services through

IHS’s Purchased/Referred Care program, IHS is the payer of last resort—that is, IHS will only pay for a service if the individual is

not eligible to have it covered by another program.

a

In managed care for Medicare and Medicaid, the federal government or states respectively contract with managed care plans to

provide a specific set of covered services to beneficiaries and pay them a set amount, typically per beneficiary per month, to provide

those services.

b

States are required to cover certain mandatory populations, such as low-income children and pregnant women, but have the option

to cover other populations, such as low-income, childless adults. As of June 2018, 33 states (including the District of Columbia)

have chosen to expand Medicaid to cover certain childless adults with incomes at or below 133 percent of the federal poverty level.

Page 5 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

IHS’s Spending Levels and Program Characteristics Vary from Those of VHA, Medicare,

and Medicaid

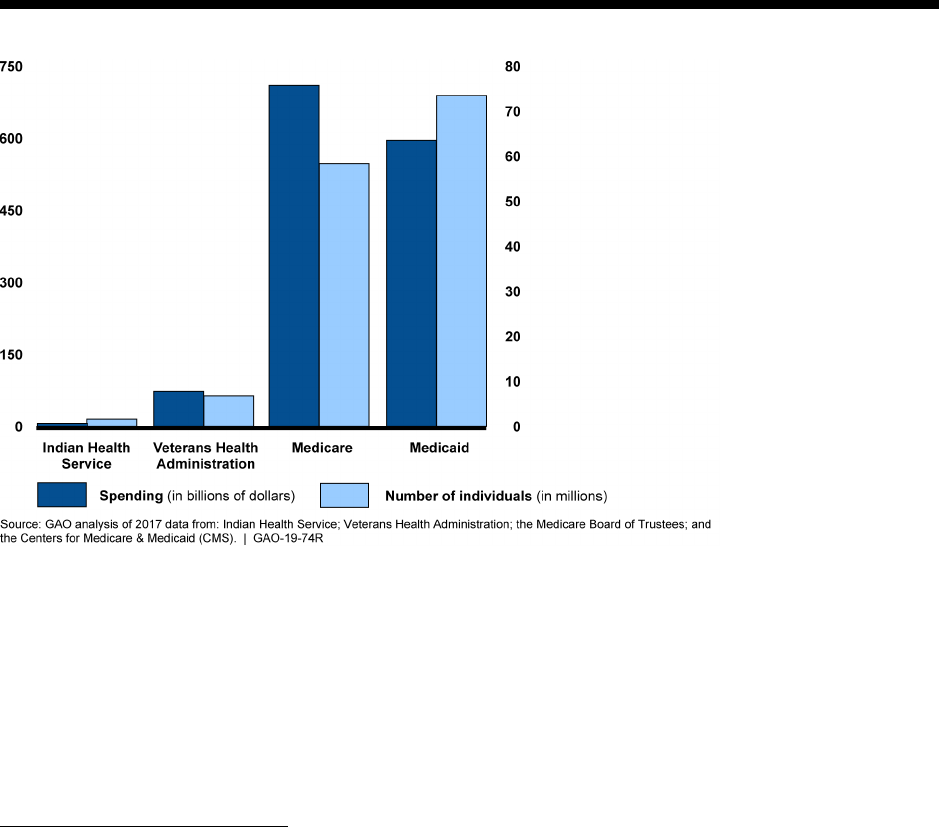

IHS is significantly smaller than VHA, Medicare, and Medicaid in terms of annual spending

levels and the number of individuals served. For example, in 2017, IHS’s total spending of $6.68

billion was less than 10 percent of VHA’s and about 1 percent of both Medicare’s and

Medicaid’s spending. In this same year, IHS served about 1.6 million individuals, about 25

percent of the number served by VHA and less than 3 percent of the number served by

Medicare and Medicaid (see fig. 1). Although spending and service levels varied over time,

these differences among the programs were also present in prior years. (See enclosures I

through IV for additional spending information about each of these four programs for 2013

through 2017.)

Figure 1: Spending Levels and Number of Individuals Served by Indian Health Service, Veterans Health

Administration, Medicare, and Medicaid, 2017

Notes: Spending levels for Indian Health Service (IHS) and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) are reported using total

obligations. IHS individuals served are those users who have accessed a federally or tribally operated facility at least once over the

past 3 years. For VHA, individuals served are “unique patients”—those uniquely identified individuals treated by VHA or whose

treatment is paid for by VHA. For Medicare and Medicaid, we report expenditures (including those by states for Medicaid), and

individuals served are beneficiaries and enrollees, respectively. Spending for Medicare represents total expenditures from the

Medicare trust funds and does not include beneficiary cost-sharing spending. The data for IHS, VHA, and Medicaid are for fiscal

year 2017, and the Medicare data are for calendar year 2017. Medicaid data are based on projections published by CMS’s Office of

the Actuary, as actual data were not yet available at the time of this report.

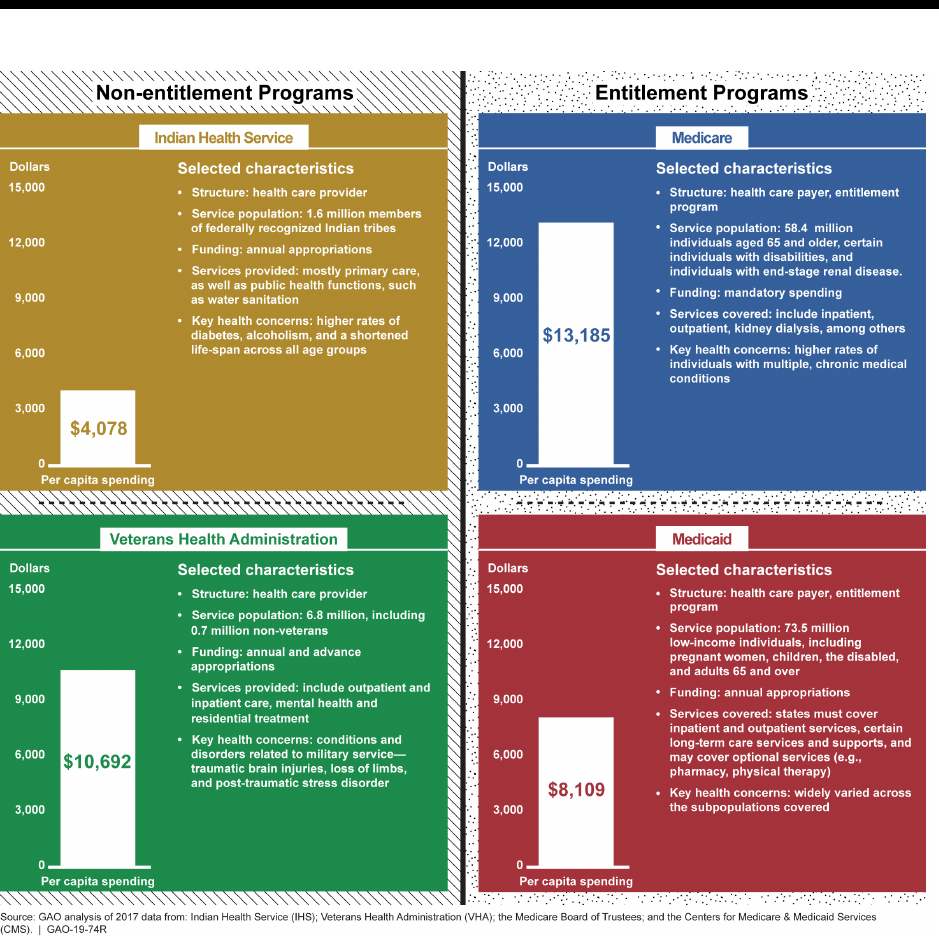

Our analysis showed that IHS’s per capita spending levels were likewise lower than those of the

other three programs.

10

For example, in 2017, IHS per capita spending was $4,078, as

compared to $8,109 for Medicaid, $10,692 for VHA, and $13,185 for Medicare.

11

In each of the

10

As discussed earlier, we calculated per capita spending as total obligations divided by the number of individuals

served for IHS and VHA, and total expenditures per individual beneficiary or enrollee for Medicare and Medicaid,

respectively. In the case of Medicaid, expenditures include spending by states.

11

We calculated IHS per capita spending using the agency’s 3-year reported user population for 2017—about 1.6

million. IHS also collects data on the number of users who accessed a facility each year—an average of about 1.3

Page 6 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

four programs, the per capita spending was relatively stable from 2013 through 2017, increasing

slightly for each program over the time period. While the per capita spending represents the

average amount of program spending per individual served, the amount does not necessarily

represent the total health spending for its beneficiaries since eligibility for one program does not

preclude eligibility for others. Therefore some individuals may receive or have services covered

through more than one program. For example, an AI/AN veteran may be eligible to receive care

from an IHS facility but may also be enrolled and eligible for care from VHA for service-

connected injuries, as well as enrolled in Medicare.

12

That individual may use the IHS facility for

primary health care and use VHA facilities or Medicare coverage for other specialty care. Total

health care spending for that individual would be captured across each of the three programs.

While examining per capita spending is one way to compare these programs, the vast

differences between IHS, VHA, Medicare, and Medicaid programs limit the applicability of such

comparisons. The programs differ in design and structure, funding, population needs, and the

services provided, for example. These fundamental differences limit the extent to which

comparisons of federal funding for each program can be used to make a determination about

the sufficiency of program funding:

• Program Design and Structure. Because IHS and VHA are direct health care providers, they

operate health care facilities and manage health care professionals as employees.

13

Medicare and Medicaid act as public insurers for their beneficiaries by reimbursing health

care providers for covered health care services. In addition, the four programs differ in how

funding is used for services beyond direct clinical care. For example, in addition to using

funding to partner with other federal agencies to build water sanitation systems, IHS

provides scholarships and loan repayment awards to recruit health professionals to serve in

areas with high provider vacancies. In the case of Medicare, a portion of the amount that it

reimburses certain facilities for care provided to patients is also intended to provide support

for physician graduate medical education at those facilities.

• Funding Mechanism. IHS and VHA funding is largely determined through the annual

appropriation process, with specific limits on the amounts that can be spent to deliver health

care services.

14

Thus, any increases in the number of people served in these two programs

absent increased funding could result in reductions in per capita spending. In contrast,

Medicare and Medicaid are entitlement programs—that is, the federal government is

required to pay for covered services for any person meeting eligibility criteria. In terms of

funding, Medicare is financed through payroll taxes, general revenues, and beneficiary

million, from fiscal years 2013 through 2017. Using this 1-year user population count, IHS’s per capita spending is

$5,173.

12

According to IHS data, in fiscal year 2017, approximately 75 percent of IHS individuals reported that they had at

least one other means of health care coverage. This estimate of the proportion of IHS users with additional coverage

is not an estimate of the extent to which they obtain services through additional coverage.

13

IHS and VHA also purchase some care from external providers.

14

Discretionary appropriations refer to those budgetary resources that are provided in appropriation acts, other than

those that fund mandatory programs. While IHS and VHA receive most of their funding from these appropriations,

they also receive mandatory spending authority for specific purposes. Mandatory spending refers to budget authority

that is provided in laws other than appropriation acts and includes entitlement authority. VA also receives advance

appropriation authority—an appropriation of new budget authority that becomes available one or more fiscal years

after the fiscal year for which the appropriation providing it is enacted. See 38 U.S.C § 117. Legislation has been

introduced in the House to provide IHS with advance appropriation authority, and we recently reported on the issue.

See GAO, Indian Health Service: Considerations Related to Providing Advance Appropriation Authority, GAO-18-652

(Washington, D.C.: Sept. 13, 2018).

Page 7 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

contributions.

15

Medicaid is financed through a combination of federal and state funding.

16

As entitlement programs, Medicare and Medicaid have no annual spending caps. Instead,

spending for Medicare and Medicaid is controlled by Congress through a modification of

benefits or changes to the way providers are paid.

• Service Availability. While each of the programs can pay for a wide variety of services, there

are differences in the actual availability of certain services. Medicare and Medicaid pay for

primary and specialty services in a variety of hospital and other settings in all parts of the

country. In contrast, IHS and VHA facilities vary in the extent to which services are available.

For example, VHA medical centers offer a variety of inpatient and outpatient services,

ranging from routine examinations to complex surgical procedures. VHA’s system also

includes facilities such as community-based outpatient clinics. In the case of IHS, most of its

facilities are smaller and may offer mostly primary and emergency care services. These IHS

facilities also tend to be located primarily in rural areas where patients and providers must

travel long distances, and where other health care providers are not available.

17

While IHS is

able to use its PRC program to pay for care not available at these facilities, the agency has

reported that PRC funds are not sufficient to pay for all necessary care and, therefore,

generally pay for only the highest priority costs, such as emergency care and transportation

to that care. (See enclosure V for more information about the PRC program.)

• Population Needs and Services Provided. The four programs serve populations with

different health needs and issues and therefore provide or pay for a wide variety of services

with varying costs. For example, while IHS has a younger population overall, its users have

higher rates of diabetes, alcoholism, and accidental deaths than the general population.

Medicare enrollees, on the other hand, tend to be older and need more in-patient care—in

addition, a subset are eligible for Medicare coverage because they have end-stage renal

disease and require ongoing kidney dialysis, a long-term and costly treatment. In each of

these programs, the needs of the population impacts the services needed, and the services

provided will impact the per capita costs.

(See fig. 2 for 2017 per capita spending levels and selected program characteristics for each of

the four federal health programs.)

15

Funds from beneficiary contributions are deposited into the Medicare trust funds that are overseen by the Medicare

Board of Trustees.

16

State Medicaid expenditures are matched by the federal government on the basis of a statutory formula. Medicaid is

considered an appropriated entitlement because, although it is an entitlement program, its funding is provided in

annual appropriation acts. CMS estimates Medicaid expenditures for the fiscal year and Congress appropriates that

amount. For the final quarter of the fiscal year, Congress also appropriates such sums as may be necessary for any

unanticipated costs.

17

We recently reported that IHS officials told us that the agency provides services almost exclusively in locations

designated by HHS’s Health Resources and Services Administration as Health Professional Shortage Areas, or

extreme shortage areas, meaning they lack sufficient number of primary care physicians. See GAO, Indian Health

Service: Agency Faces Ongoing Challenges Filling Provider Vacancies, GAO-18-580 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 15,

2018).

Page 8 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Figure 2: 2017 Per Capita Spending Levels and Selected Program Characteristics for Four Federal Health

Programs: Indian Health Service, Veterans Health Administration, Medicaid, and Medicare

Notes: Some individuals may receive or have services covered through more than one program; however, the reported per capita

spending amounts do not account for spending across multiple programs. While IHS and VHA receive most of their funding from

annual appropriations, they also received mandatory amounts for specific purposes. For IHS we calculated per capita spending as

total obligations divided by the number of individuals served. IHS defines individuals served as those who have accessed a federally

or tribally operated facility at least once over the past 3 years. For VHA, the per capita spending represents obligations per unique

patient (uniquely identified individuals treated by VHA or whose treatment is paid for by VHA). For Medicare and Medicaid, we report

on expenditures (including those by states for Medicaid) by the number of individuals served. Spending for Medicare represents

total expenditures from the Medicare trust funds and does not include beneficiary cost-sharing spending. The data for IHS, VHA,

and Medicaid are for fiscal year 2017, and the Medicare data are for calendar year 2017. The Medicaid data are based on estimates

published by CMS’s Office of the Actuary, as actual data were not yet available at the time of this report.

Page 9 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS and VA. Both departments provided us with technical

comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

_ _ _ _ _

We are sending copies of this report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Secretary

of Veterans Affairs, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge

on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staffs have any questions about this information, please contact me at (202) 512-

7114 or [email protected]. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public

Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to

this report were William D. Hadley, Assistant Director; Kristeen McLain, Analyst-in-Charge;

Manuel Buentello; and Keith Haddock. Also contributing were Muriel Brown, Jackie Hamilton,

Laurie Pachter, and Vikki Porter.

Jessica Farb

Director, Health Care

Enclosures – 5

Page 10 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Enclosure I: Indian Health Service

Enclosure I

Indian Health Service

Annual Spending and Numbers Served

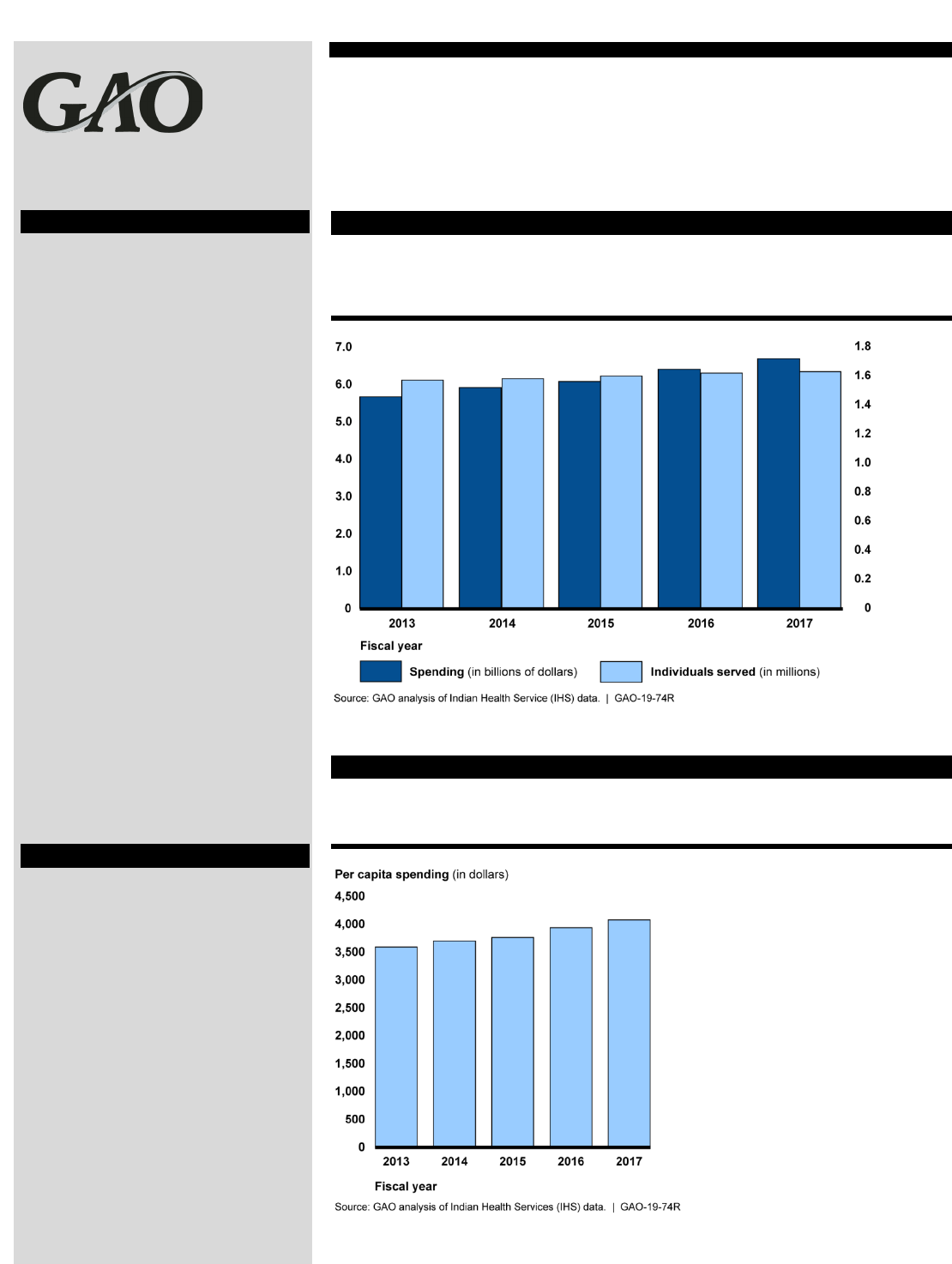

According to our analysis, from fiscal years 2013 through 2017, IHS’s

annual spending increased from $5.66 billion to $6.68 billion (18 percent),

while the annual population served remained around 1.6 million.

Figure 3: IHS Spending and Number of Individuals Served, Fiscal Years 2013-2017

Notes: Spending is in total obligations. Individuals served are referred to as “users” by IHS, and are

defined as a person who has accessed IHS at least once over the past 3 years.

Per Capita Spending

Over the past five fiscal years, IHS’s per capita spending increased from

$3,591 to $4,078 (14 percent).

Figure 4: IHS Per Capita Spending, Fiscal Years 2013-2017

Notes: To calculate per capita spending, we analyzed IHS’s total obligations. We then divided the

spending amount by the number of individuals served, which are defined by IHS as a person who has

accessed services at least once over the past 3 years.

Program Overview

The Indian Health Service (IHS)

was established within the Public

Health Service in 1955 to provide

health services to American Indian

and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people.

IHS provides services directly

through a network of 26 hospitals,

53 health centers, and 30 health

stations in 37 U.S. states, primarily

in rural areas on or near

reservations. IHS also awards

contracts and grants to non-profit

urban Indian organizations that

provide health care and referral

services to urban Indians. IHS also

funds services provided at tribally

operated facilities. In fiscal year

2017, about 54 percent of IHS

funds went to tribal organizations.

In certain circumstances, IHS pays

for services provided by external

providers through its

Purchased/Referred Care program.

In addition to the provision of

health care, IHS performs several

public health functions, including

public health nursing and water

sanitation facility construction.

How Funded

IHS is largely funded through

discretionary appropriations, but

also receives some funding

through reimbursements from other

federal programs such as

Medicaid, Medicare, and the

Veterans Health Administration, as

well as private insurance. IHS also

receives mandatory spending

authority (around $150 million

annually) to support Special

Diabetes Programs for Indians.

Page 11 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Enclosure I: Indian Health Service

Enclosure I

Indian Health Service (con’t.)

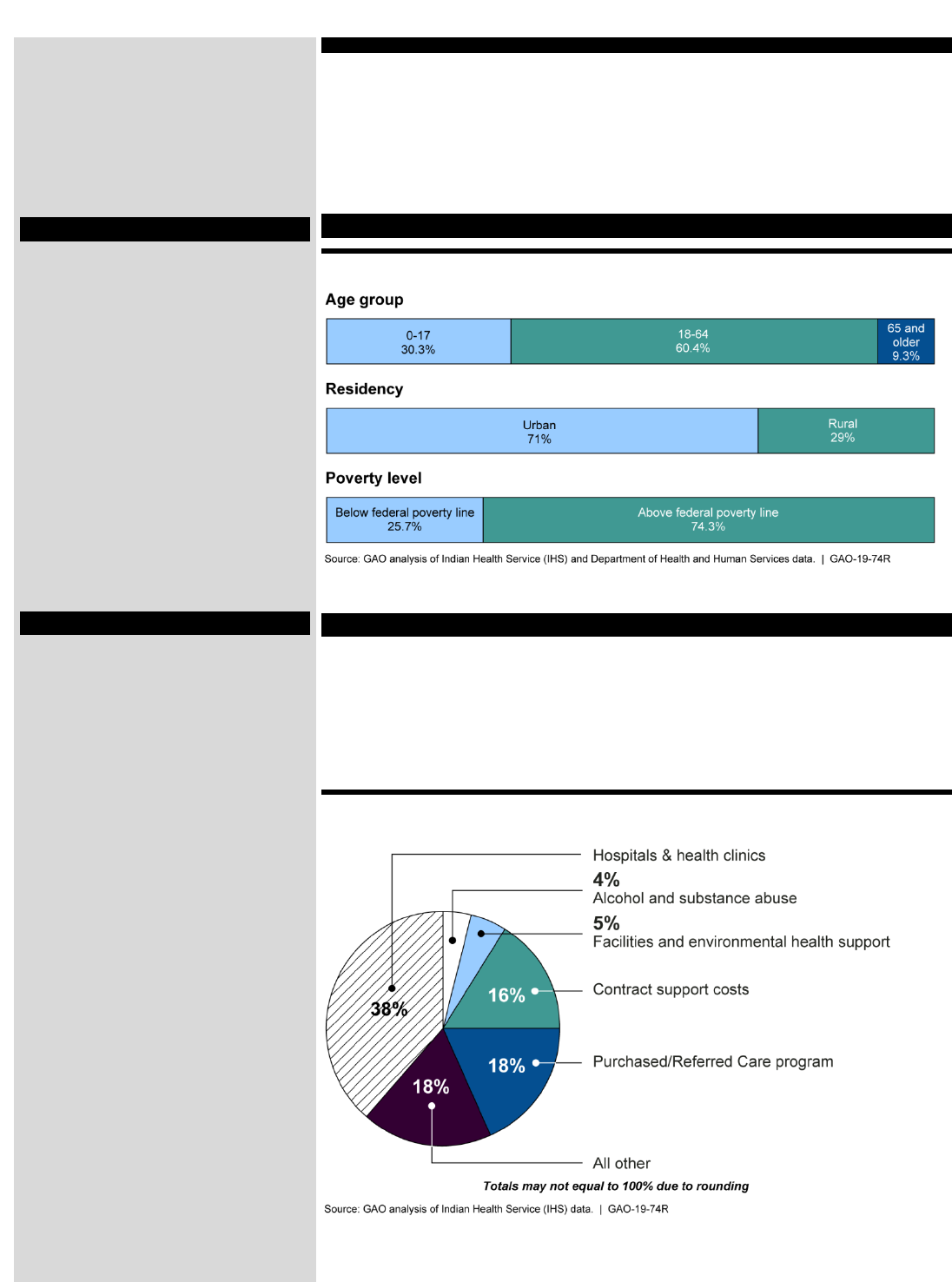

User Characteristics

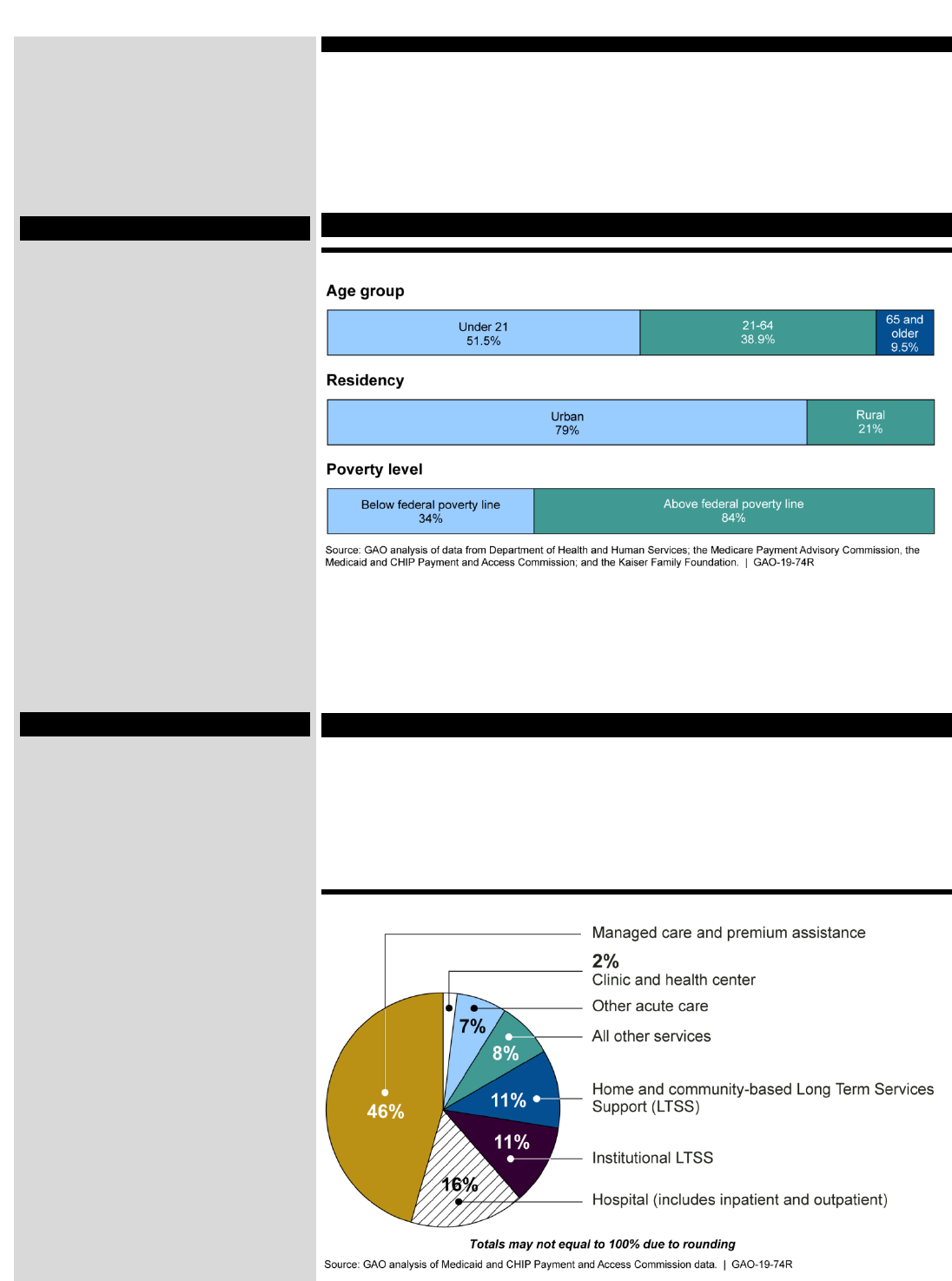

Figure 5: Selected Characteristics of IHS Users

Notes: Age group data are fiscal year 2017, residency data are calendar year 2010, and poverty data

are calendar year 2000.

Services

According to our analysis, in fiscal year 2017, just over one-third of IHS's

budget was allocated to hospitals and health clinic services. IHS also

funded several service categories outside direct health care. For

example, 16 percent of funds were allocated to contract support costs—

supporting required activities that ensure tribes’ compliance with their

self-governance agreements.

Figure 6: IHS Services Provided by Percentage of Funding, Fiscal Year 2017

Notes: Funding for services is measured in budget authority. IHS’s Purchased/Referred Care

program pays for care when those services are not available at federally operated or tribally operated

IHS facilities. Contract support costs cover required activities to ensure compliance with their self-

determination contracts and self-governance compacts.

Eligibility

IHS users generally must be a

member or descendant of one of

the 573 currently federally

recognized Indian tribes belonging

to the Indian community, as

evidenced by such factors as

membership, residence on tax-

exempt land, active participation in

tribal affairs, or other relevant

factors. IHS services are provided

free to eligible IHS users and there

are no cost-sharing requirements.

Health Issues

According to IHS, AI/AN people die

at higher rates in many categories,

including chronic liver disease and

cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus,

unintentional injuries, assault or

homicide, intentional self-harm or

suicide, and chronic lower

respiratory diseases.

IHS provides a number of health

services that target common health

conditions among beneficiaries,

such as diabetes prevention and

treatment, and behavioral health

services including suicide

prevention and methamphetamine

treatment.

Page 12 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Enclosure II: Veterans Health Administration

Enclosure II

Veterans Health Administration

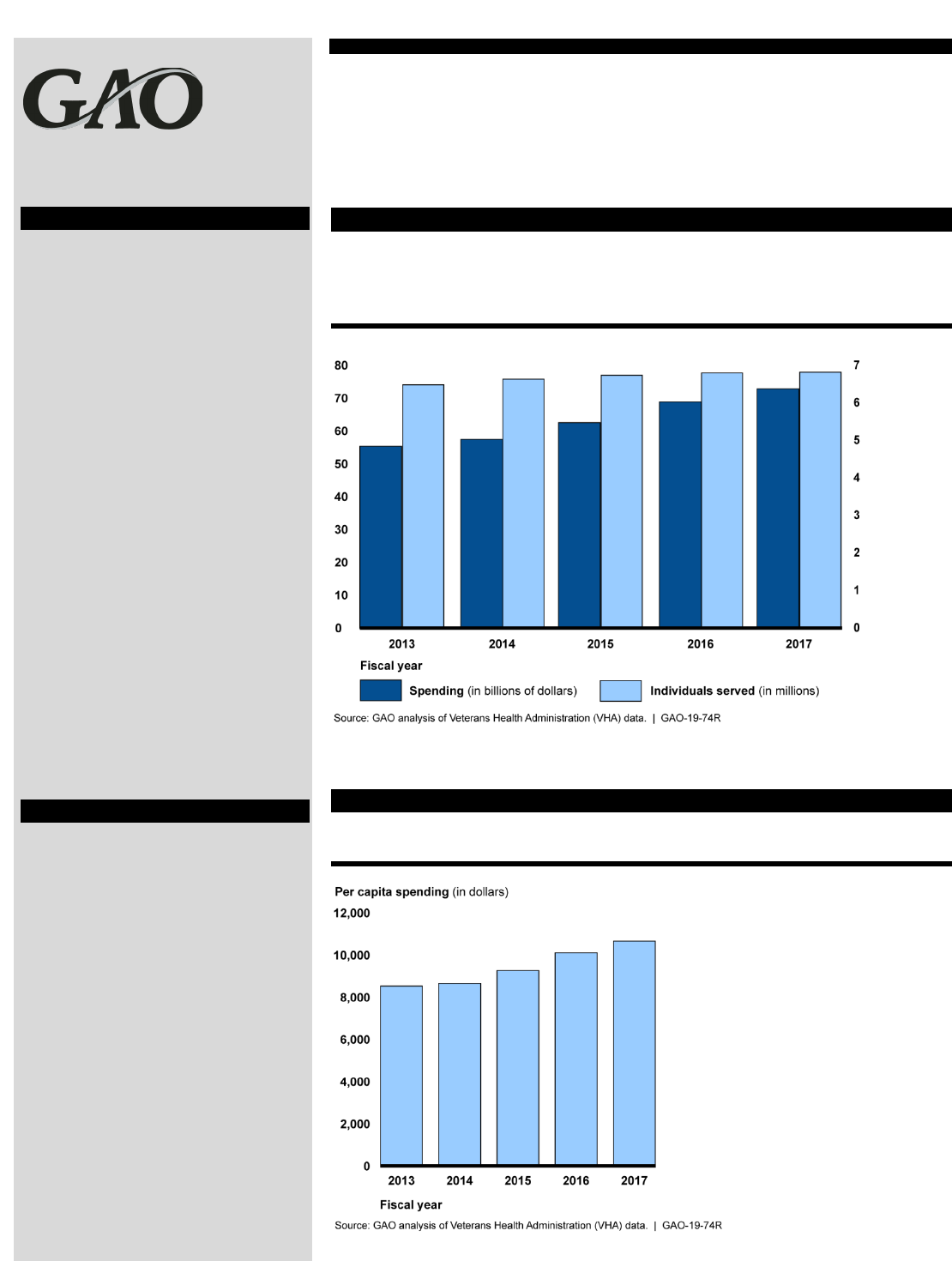

Annual Spending and Numbers Served

According to our analysis, from fiscal years 2013 through 2017, VHA’s

annual spending level increased from $55 to $73 billion (32 percent),

while the number of individuals served increased from 6.5 million to 6.8

million (5 percent).

Figure 7: VHA Spending and Number of Individuals Served, Fiscal Years 2013-2017

Note: Spending represents total obligations per fiscal year. Individuals served are “unique patients”

and represent uniquely identified individuals treated by VHA or whose treatment is paid for by VHA

expenditures.

Per Capita Spending

Over the past five fiscal years, per capita spending for VHA increased

from $8,551 to $10,692 (25 percent).

Figure 8: VHA Per Capita Spending, Fiscal Years 2013-2017

Note: Spending per capita represents total obligations per unique patient—uniquely identified

individuals treated by VHA or whose treatment is paid for by VHA expenditures.

Program Overview

The Veterans Health

Administration (VHA), part of the

Department of Veterans Affairs

(VA), established a network of

facilities to provide health care to

veterans, in particular to help them

recover from illnesses and injuries

sustained in service to the country.

In addition to providing services

through agency-administered

facilities—hospitals, outpatient

clinics, and nursing homes—VHA

can also pay for services outside

its health care system for eligible

veterans through its community

care programs when care is not

readily available at its medical

facilities.

How Funded

The VHA program is largely funded

through discretionary

appropriations. VA (which oversees

VHA) also receives advance

appropriations—an appropriation of

new budget authority that becomes

available one or more fiscal years

after the fiscal year for which the

appropriation providing it is

enacted—for specified medical

care accounts. In addition, VHA

can be reimbursed by private

insurance for services that are not

service-connected. While VHA

users do not pay premiums, some

users may have to pay copayments

for certain medical services.

Page 13 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Enclosure II: Veterans Health Administration

Enclosure II

Veterans Health Administration (con’t.)

User Characteristics

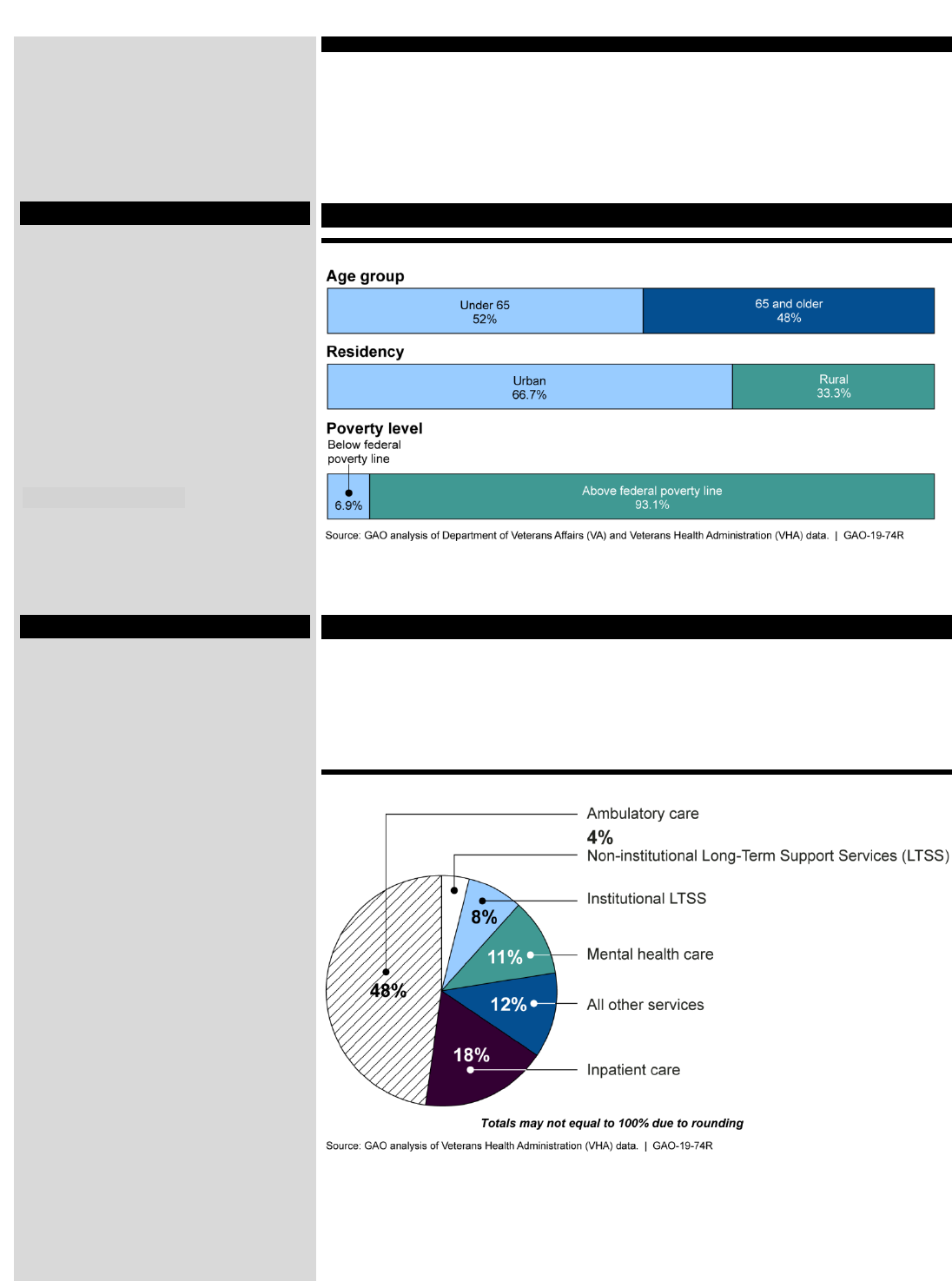

Figure 9: Selected Characteristics of the Veteran Population

Note: The age group and residency data represent VHA’s unique patient populations for fiscal year

2017 and fiscal year 2015, respectively. The poverty data represent the total veterans population, and

are based on a 3-year period estimate, 2010 through 2012.

Services

VHA’s health care system provides enrolled veterans with a full range of

services including primary care, mental health, inpatient care, and

residential treatment. In fiscal year 2017, close to half of the expenditures

for services provided by VHA were for ambulatory (outpatient) care,

according to our analysis.

Figure 10: VHA Services Provided by Expenditures, Fiscal Year 2017

Eligibilty

Eligibility for services provided

through the VHA is based on

several factors, including the

veteran’s period of active service,

discharge status, and the presence

of service connected disabilities. In

addition, VHA categorizes eligible

veterans into eight priority groups

that determine the type of services

the veteran can access, and that

have implications for cost-sharing.

Eligibility for VHA’s community

care programs vary.

Health Issues

VHA focuses on conditions and

disorders related to military service

and war, including traumatic brain

injuries, post-traumatic stress

disorder, mental health issues,

such as suicide prevention, and

loss of limbs.

Page 14 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Enclosure III: Medicare

Enclosure III

Medicare

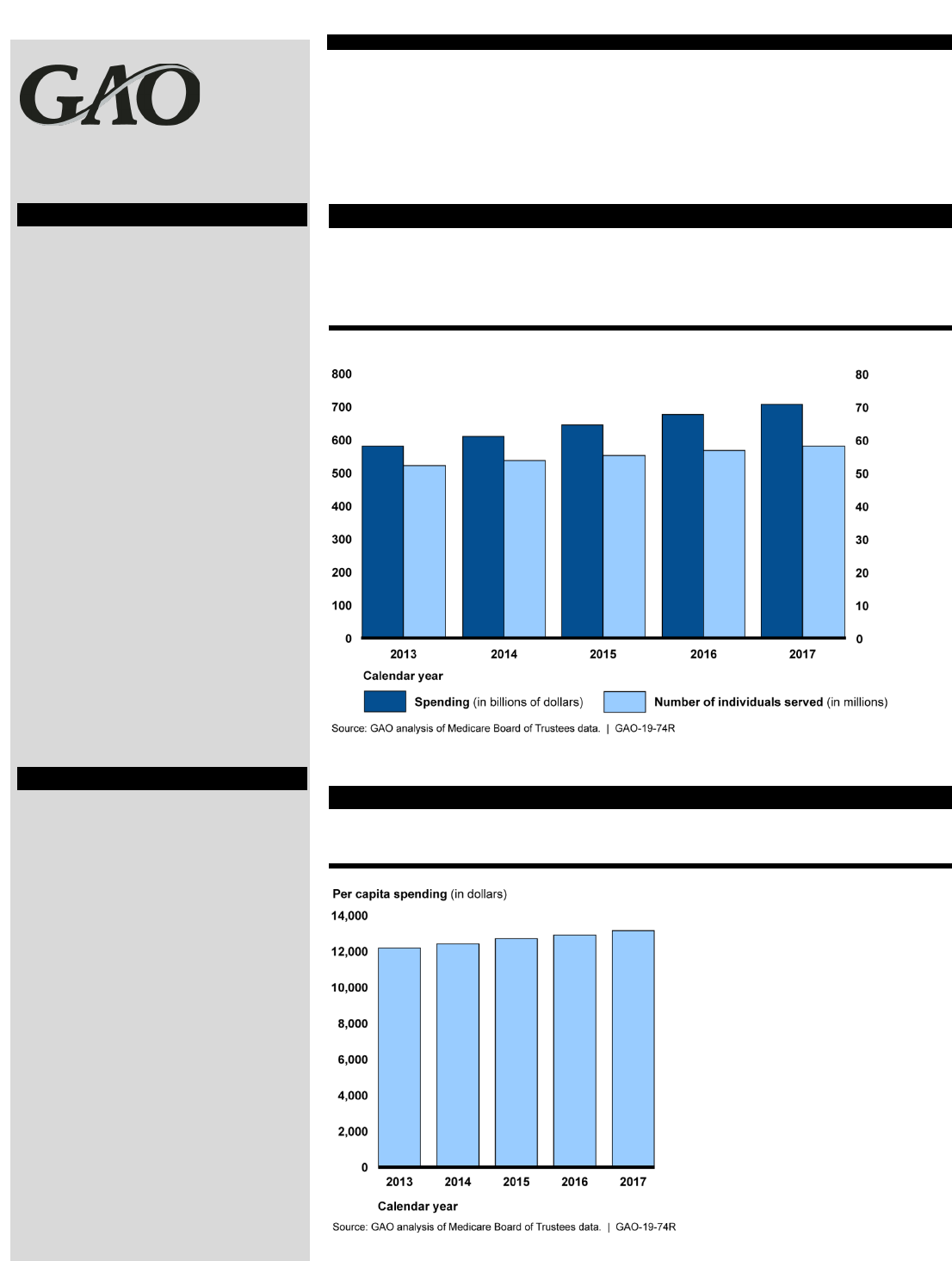

Annual Spending and Numbers Served

According to our analysis, from calendar years 2013 through 2017

Medicare spending increased by 22 percent, from $583 billion to $710

billion. During that same period, the number of individuals served grew

about half as much, by 10 percent.

Figure 11: Medicare Spending and Number of Individuals Served, Calendar Years

2013-2017

Note: Spending represents total expenditures from the Medicare trust funds and does not include

beneficiary cost-sharing spending. Individuals served are Medicare beneficiaries.

Per Capita Spending

Over the past five calendar years, Medicare per capita spending

increased from $12,218 to $13,185 (8 percent).

Figure 12: Medicare Per Capita Spending, Calendar Years 2013-2017

Note: Per capita spending represents average expenditures from the Medicare trust funds, and does

not include beneficiary cost-sharing spending.

Program Overview

The Medicare program, established

under Title XVIII of the Social

Security Act in 1965, pays for

health services for individuals 65

and older and individuals with

certain disabilities and conditions.

The program is administered by the

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services (CMS) within the U.S.

Department of Health and Human

Services. Medicare consists of four

distinct parts (A through D). Part A

covers inpatient hospital services,

skilled nursing care, hospice care,

and some home health services.

Part B covers physician services,

outpatient services, and some

home health and preventive

services. Part C (Medicare

Advantage) is a private plan option

for beneficiaries, and covers all

Parts A and B services except

hospice. Lastly, Part D covers

outpatient prescription drug

benefits.

How Funded

Medicare is funded through payroll

taxes paid by employees and

employers, general revenues, and

interest on the Medicare trust

funds. Medicare is also funded

through premiums paid by

beneficiaries. Beneficiaries also are

responsible for cost sharing—

deductibles and co-payments—for

covered services. Medicare is an

entitlement program and required

to pay for all covered services

provided to eligible persons, so

long as specific criteria are met.

Thus, spending under the program

(except for a portion of

administrative costs) is considered

mandatory and is not subject to

spending caps in appropriation

acts.

Page 15 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Enclosure III: Medicare

Enclosure III

Medicare (con’t.)

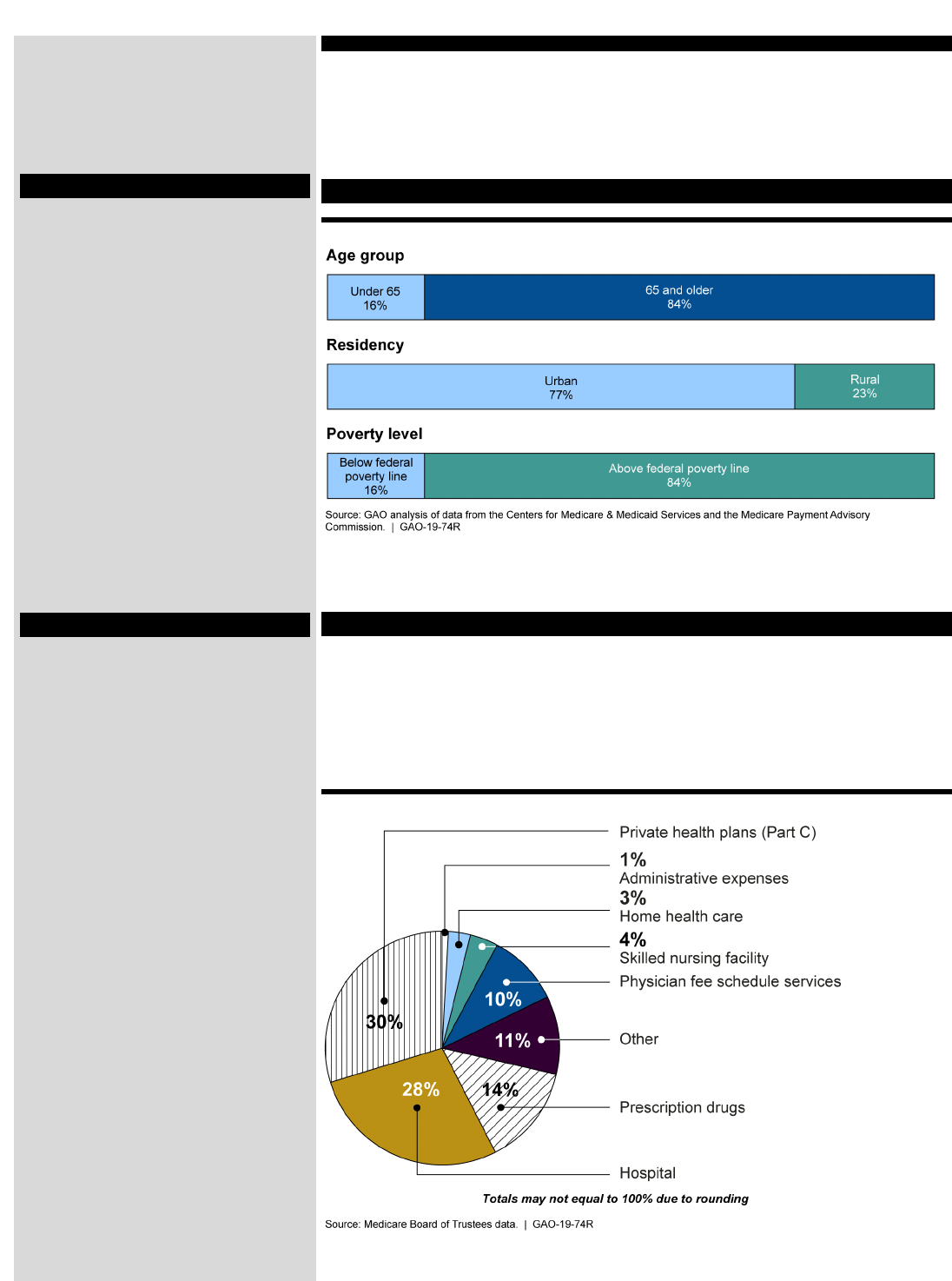

User Characteristics

Figure 13: Selected Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries

Notes: The age group and residency data represent the Medicare beneficiary population for calendar

year 2015 and 2013, respectively. The poverty data represent calendar year 2013.

Services

The Medicare program covers a wide variety of services, including

inpatient and outpatient care, some home health and preventive services,

and prescription drug benefits. In calendar year 2017, our analysis

showed that 30 percent of Medicare spending was for Part C (Medicare

Advantage), followed by hospital care (28 percent) and prescription drugs

(14 percent).

Figure 14: Medicare Services by Percentage of Expenditures, Calendar Year 2017

Note: These expenditures exclude cost-sharing spending by Medicare beneficiaries.

Eligibility

Generally, individuals are eligible

for Medicare if they or their spouse

worked for at least 40 quarters in

Medicare-covered employment,

are 65 years old, and are a citizen

or permanent resident of the

United States. Younger individuals

who have been eligible for Social

Security benefits for 24 months are

also eligible, as are those who

have end-stage renal disease

(permanent kidney failure requiring

dialysis or transplant), or have

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS,

Lou Gehrig’s disease).

Health Issues

Medicare serves approximately

one in six Americans and virtually

all of the population aged 65 and

older. Leading causes of death

among people 65 and over have

remained the same over the past

few decades, with heart disease

and cancer remaining at the top

followed by chronic respiratory

issues and stroke. In addition, the

Medicare population has high rates

of individuals with multiple, chronic

medical conditions.

Page 16 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Enclosure IV: Medicaid

Enclosure IV

Medica

id

Annual Spending and Numbers Served

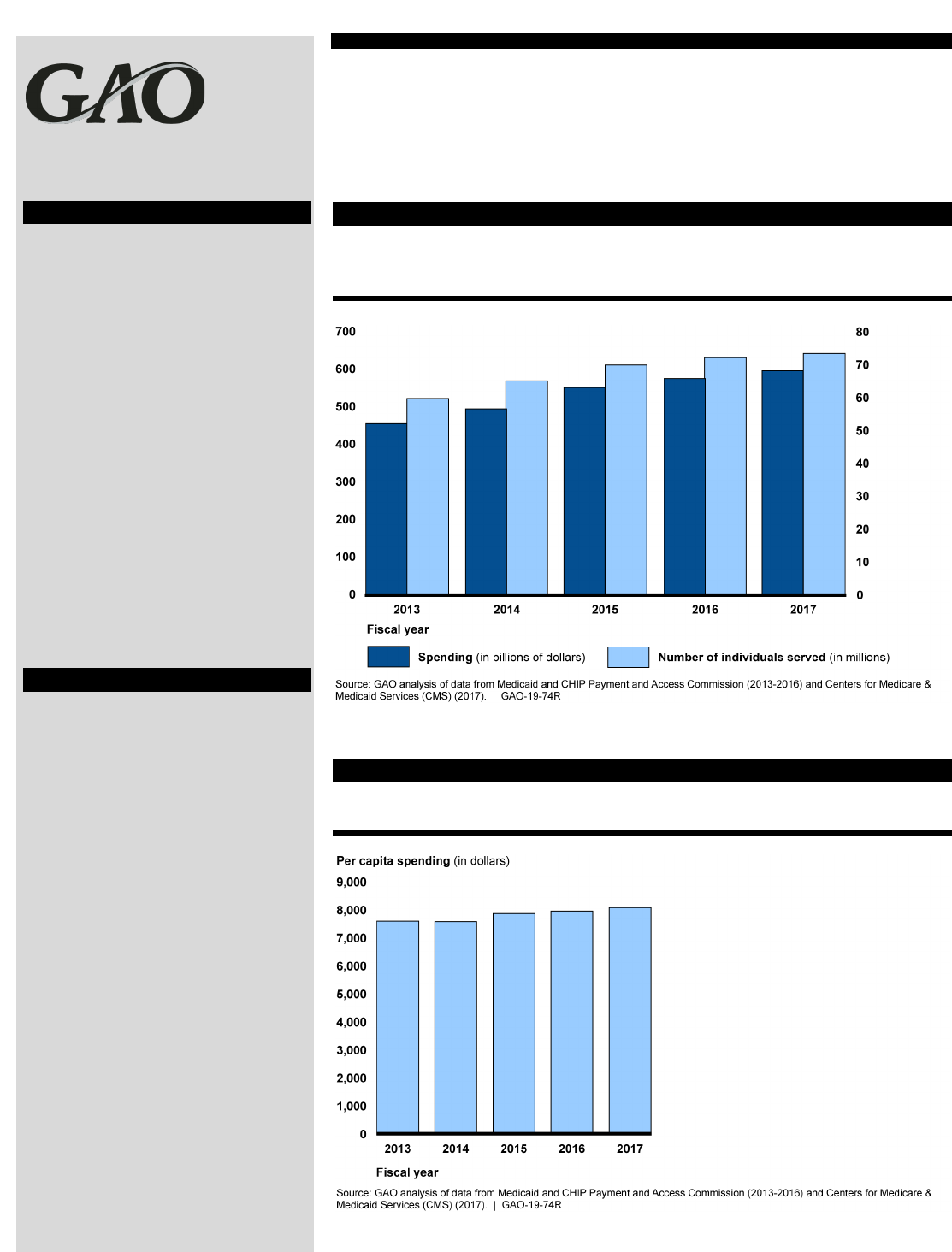

According to our analysis, from fiscal years 2013 through 2017, Medicaid

spending increased from $456 billion to $596 billion (31 percent), while

enrollment grew from 59.8 million to 73.5 million (23 percent).

Figure 15: Medicaid Spending and Number of Enrollees, Fiscal Years 2013-2017

Notes: Spending consists of federal and state Medicaid expenditures for benefits and administration,

excluding the Vaccines for Children program. Enrollment counts are full-year equivalents. Data for

fiscal year 2017 are based on CMS estimates and were the most recent available.

Per Capita Spending

Over the past five fiscal years, Medicaid spending per capita increased

from $7,615 in to $8,109 (6 percent).

Figure 16: Medicaid Per Capita Spending, Fiscal Years 2013-2017

Notes: Spending consists of federal and state Medicaid expenditures for benefits and administration,

excluding the Vaccines for Children program. Enrollment counts are full-year equivalents. Data for

fiscal year 2017 are based on CMS estimates and were the most recent available.

Program Overview

Medicaid—a joint federal-state

health financing program for low-

income and medically needy

individuals—was authorized by

Title XIX of the Social Security Act

in 1965. The Centers for Medicare

& Medicaid Services (CMS)

oversees states’ administration of

Medicaid. States are allowed

flexibility to design and implement

their programs within broad federal

parameters, resulting in variation in

eligibility and services covered

across the states.

How Funded

The federal government and states

share in the financing of Medicaid

expenditures, with the federal

government matching most state

expenditures for services on the

basis of a statutory formula, known

as the federal medical assistance

percentage. The federal share of

Medicaid expenditures typically

ranges from 50 to 83 percent.

Funding for Medicaid is provided in

annual appropriations acts, but is

not subject to specific dollar limits.

Page 17 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Enclosure IV: Medicaid

Enclosure IV

Medicaid (con’t.)

User Characteristics

Figure 17: Selected Characteristics of Medicaid Enrollees

Notes: The age group and residency data represent Medicaid enrollee population for fiscal year 2013

and calendar year 2013, respectfully. The residency data exclude nondisabled enrollees under age

65, and those ages 65 and older who did not have Medicare coverage. The poverty data represent

Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on Census Bureau data, 2014-2017.

Services

Medicaid provides a wide variety of services in order to provide care for

its diverse enrollee population, that includes children, adults, the disabled,

and the elderly. In fiscal year 2016, spending on managed care and

premium assistance made up almost 50 percent of total Medicaid

expenditures, followed by hospital services (both inpatient and outpatient)

at 16 percent.

Figure 18: Medicaid Services, by Expenditures, Fiscal Year 2016

Eligibility

Eligibility for Medicaid varies

across states. Federal law requires

states to cover certain populations

and gives them the flexibility to

cover others. Mandatory

populations include low-income

children and families, pregnant

women, and aged, blind and

disabled individuals. States may

also cover other populations. For

example, under the Patient

Protection and Affordable Care

Act, states may expand their

Medicaid programs to cover

childless, non-elderly low-income

adults. Medicaid enrollment is

therefore expected to grow by as

many as 13.2 million newly eligible

adults by 2025.

Health Issues

Health concerns vary considerably

among the different Medicaid

populations. For example, the

health concerns for children

enrolled in Medicaid center on

primary and preventive care, with a

small proportion requiring

medically complex care. In

contrast, Medicaid beneficiaries

who qualify on the basis of a

disability may have conditions such

as traumatic brain injuries,

intellectual or developmental

disabilities (such as cerebral palsy)

or serious behavioral disorders or

mental illness (such as

schizophrenia), all of which require

longer-term and high-cost care.

Page 18 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Enclosure V: Indian Health Service’s Purchased/Referred Care Program

When an Indian Health Service (IHS) user needs health care services that are not available

from providers at a federal or tribal facility, the IHS Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) program

pays for services from external providers. Eligibility requirements for the PRC program are more

restrictive than for services provided directly through a facility, and all PRC requests are

categorized according to a medical priority system to help ensure that the program funds

services for the most serious medical conditions.

18

Therefore, not all requests for PRC program

funding are approved.

We obtained and analyzed data from IHS on the PRC program for fiscal years 2013 through

2017, including the expenditures and type of services paid through federally administered

facilities. We also analyzed the number of requests for payment that were not approved. These

data represent federally operated facilities—which in fiscal year 2017 represented about 46

percent of all IHS expenditures—and some tribally operated facilities, which are encouraged,

but not required, to report such data. We performed data reliability checks, such as checks for

internal consistency on total services and comparison of service expenditures to the PRC

program budgets, and determined the PRC program data were sufficiently reliable for our

purposes.

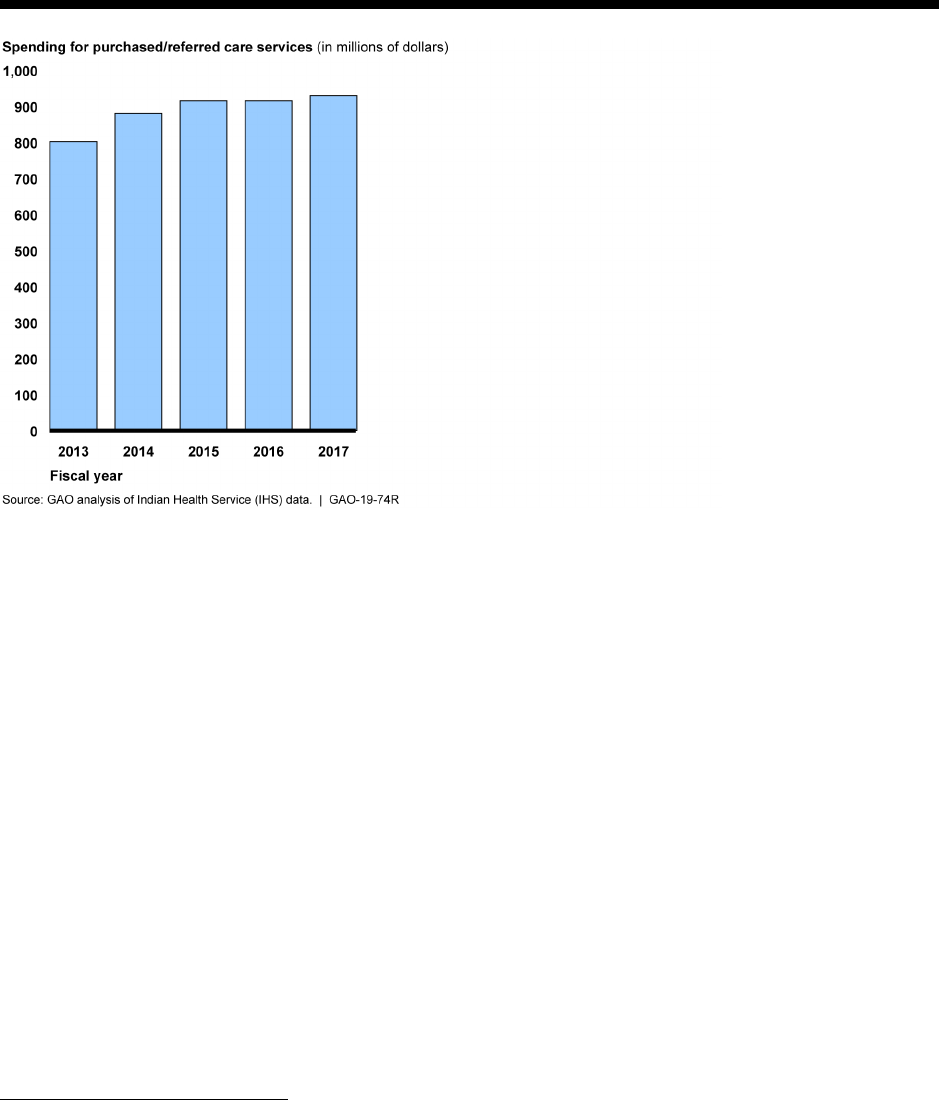

PRC Program Spending and Services

The PRC program is funded through the annual appropriations process, and available funds are

distributed to federally and tribally operated facilities based on a formula.

19

Spending for the

PRC program grew from $801 million in fiscal year 2013 to $929 million in fiscal year 2017, an

increase of 16 percent. (See fig. 19.)

18

IHS’s medical priority levels are: (1) Emergent or Acutely Urgent Care Services; (2) Preventive Care Services; (3)

Primary and Secondary Care Services; (4) Chronic Tertiary Care Services; and (5) Excluded Services. IHS users

who receive services paid through the PRC program must live within a specific geographic area for each facility;

these areas are smaller than other IHS service areas. Furthermore, the IHS user must also demonstrate that other

health care resources are not available to pay for the needed services.

19

See GAO, Indian Health Service: Action Needed to Ensure Equitable Allocation of the Resources for the Contract

Health Service Program GAO-12-446 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 15, 2012). “Contract Health Service Program” is the

former name of the PRC program. In addition to receiving federal funding through IHS, the tribes may provide

supplemental funds to the PRC programs they administer.

Page 19 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Figure 19: Indian Health Service Purchased/Referred Care Spending, Fiscal Years 2013-2017

Facilities can use PRC program funds to pay for a wide variety of services not available in the

facility. Between fiscal years 2013 and 2017 PRC program expenditures associated with

inpatient services ranged from 36 to 45 percent.

20

During that same period, outpatient services

expenditures ranged from 43 to 51 percent and patient transportation expenditures were 10 to

11 percent of expenditures.

21

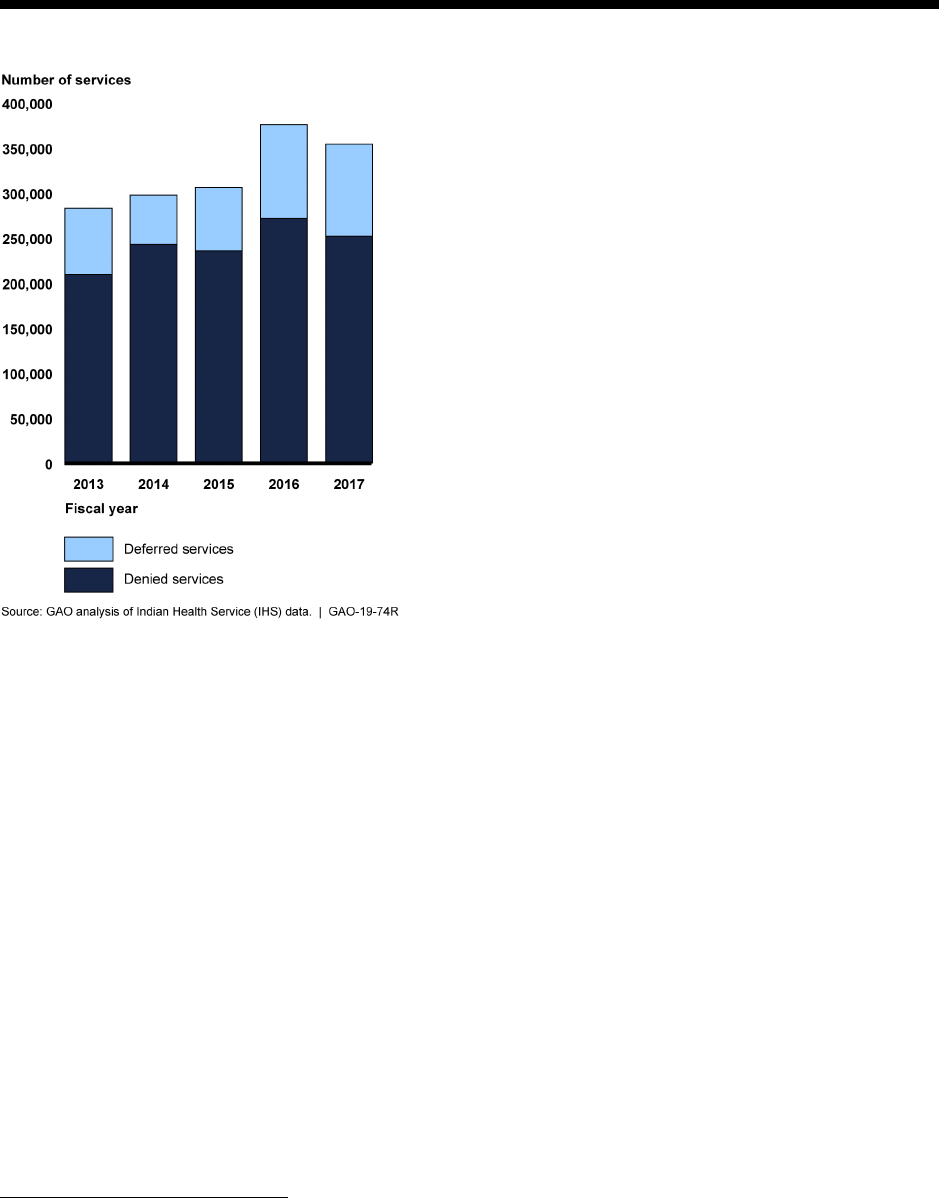

Not All Requests for PRC Services Are Funded

Facilities do not approve all requests for services made through the PRC program. Requests

may be denied because the user did not meet PRC eligibility requirements, or because the

services were not within the medical priority for which funding is available. A facility may also

defer requests to pay for services until funding becomes available.

22

The number of deferred and denied services in federally and tribally operated facilities grew

from 283,020 services overall in fiscal year 2013 to 354,446 services in fiscal year 2017, an

increase of about 25 percent. (See fig. 20.) The majority of these services were categorized as

denials.

20

As discussed earlier, available IHS data on PRC program expenditures are limited to those facilities that are

federally operated, which in fiscal year 2017 represented about 46 percent of all IHS expenditures. The remaining

facilities were tribally operated and are not required to report these data to IHS.

21

According to IHS, IHS users living in rural areas often have to travel long distances for referral services.

22

IHS policy requires that deferred services be for elective care, rather than emergent or urgent care. Programs may

not defer payment for services already rendered, only for services that have not been received.

Page 20 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Figure 20: Number of Denied and Deferred Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) Program Services (Federal and

Tribal), Fiscal Years 2013-2017

Note: Data represent PRC program requests from federally operated facilities—which in fiscal year 2017 represented about 46

percent of all IHS expenditures—and some tribally operated facilities, which are encouraged, but not required to report such data.

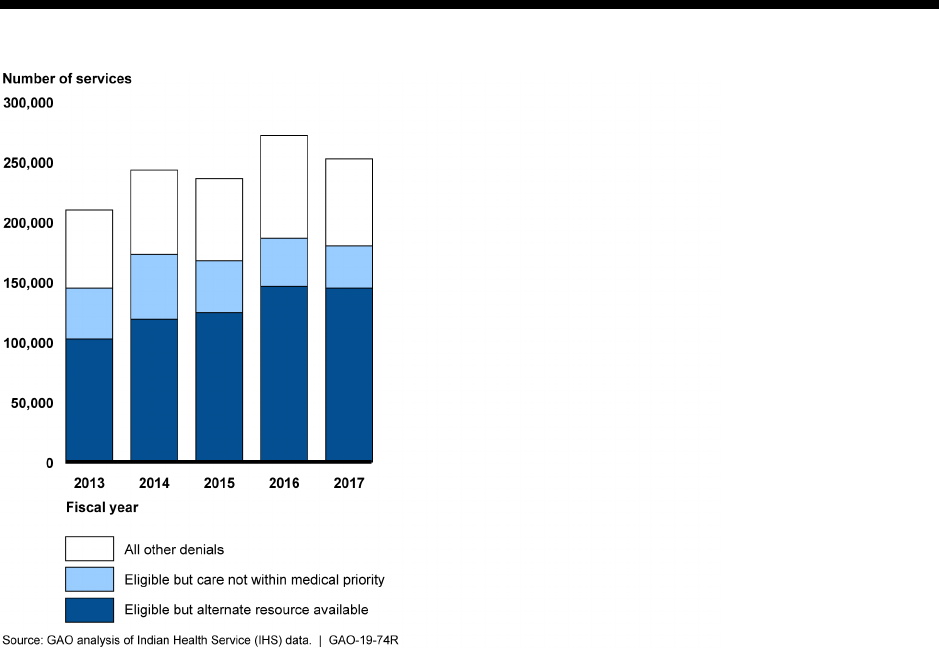

Federally and tribally operated facilities reported a variety of reasons for why services under the

PRC program were denied. The most common reason for the denial from fiscal years 2013

through 2017 was that the user had an alternate source of coverage for the service—such as

Medicaid or private insurance—to pay for the service, increasing from 102,409 denied requests

in fiscal year 2013 to 144,655 denied requests in fiscal year 2017. (See fig. 21.) The second

most common reason for denial under the PRC program was that the user’s needed health care

services were not within the medical priorities for which the facility had funding, although the

user was otherwise eligible.

23

Specifically, that reason accounted for 42,293 denials in fiscal

year 2013 and decreased to 34,988 denials in fiscal year 2017.

Those denied services included,

among others, inpatient services, outpatient services, and transportation services.

23

We found that facilities have often been limited to paying for only those services within the first category of the

medical priority system—emergency services to prevent the immediate death or serious impairment of the health of

the individual. See GAO-12-446. However, some facilities are able to pay for additional types of services.

Page 21 GAO-19-74R Indian Health Service

Figure 21: Number of Denied Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) Program Services (Federal and Tribal) by

Reason, Fiscal Years 2013-2017

Note: “All other denials” includes reasons such as emergency notification not provided within 72 hours and the patient residing

outside the PRC service delivery area, among others. Data represent PRC program requests from federally operated facilities—

which in fiscal year 2017 represented about 46 percent of all IHS expenditures—and some tribally operated facilities, which are

encouraged, but not required to report such data.

(102489)

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States.

The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission

from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material,

permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material

separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative

arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional

responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the

federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public

funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses,

recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed

oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government

is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is

through GAO’s website (https://www.gao.gov). Each weekday afternoon, GAO

posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. To

have GAO e-mail you a list of newly posted products, go to https://www.gao.gov

and select “E-mail Updates.”

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and

distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether

the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering

information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077, or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard,

Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or E-mail Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

Contact:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/fraudnet/fraudnet.htm

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7470

Orice Williams Brown, Managing Director, WilliamsO@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400,

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125,

Washington, DC 20548

Chuck Young, Managing Director, young[email protected], (202) 512-4800

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

James-Christian Blockwood, Managing Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814,

Washington, DC 20548

GAO’s Mission

Obtaining Copies of

GAO Reports and

Testimony

Order by Phone

Connect with GAO

To Report Fraud,

Waste, and Abuse in

Federal Programs

Congressional

Relations

Public Affairs

Strategic Planning and

External Liaison

Please Print on Recycled Paper.